Look and learn: verbless clauses part 1

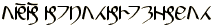

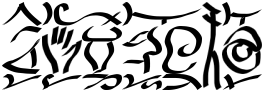

satexankitolpas. àke!tiáxesêfussiòisetehnatis. àke!tiáfushne! nilákiskinyfekhnest. àke!siáfixstiskiỳfakkátankitapas. cirivz àke!fiétap fysake!. òiqykxiàke!tiỳfuxeèipashriàke!tinycyt ovz nykosshrake!tinykykêcicenycicxihnke!. sake!siòisetxiàke!ehnil evz sake!slacushne!

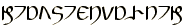

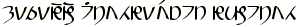

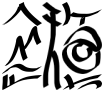

satexankitolpas sæteʃænkitɑlpæs satex .an .ki .tolpas SG.rock .NAME .M-ASSC .PL.this This is Peter

Using demonstratives

The most common use for demonstratives are: to introduce a new person or object into the discourse and signal that you plan to assign them to a spare personal object (more common in writing than in talking); and to answer questions or add heavy emphasis to a particular person or object.

In this instance, the inclusion tells the reader that 'Peter' will be assigned to the next available personal object - in this case the natural things third person singular àke!, which is generally the first to be assigned.

Unlike in Ramajal, the demonstrative does not need to agree with its object (this goose, these geese). This is because the demonstrative object tapas is a mass object, with each of its numbers meaning a different thing: tapas - 'the'; telpas - 'a', 'some'; tolpas - 'this', 'these'; tyhnpas - 'that', 'those'; tupas - 'not this', 'not these', 'not that', 'not those'.

Ákat has a second set of demonstrative objects based on the word nytyf (specific), used to single out a particular object from a group (this particular goose, those particular geese): nutyf - 'that', distant from both speaker and listener; natyf - 'that', close to listener; neityf - 'this', close to speaker; noityf - 'specific', 'particular' (location not determined).

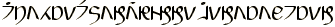

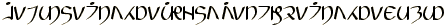

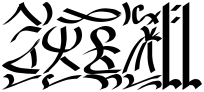

àke!tiáxesêfussiòisetehnatis jækeʔtiwæʃesɜfʊssijɑiseteŋætis àke! .ti .áxesêfus .si .òiset .e .hnatis he.1 .M-ASSG .SG.boy .M-EPHM .PL.year .M-CONC .sixteen He[P] is a boy, aged 16

Objects with multiple modifiers

In the above one-word sentence, the head object àke! is followed by three modifying objects:

- the first modifier object is tiáxesêfus - in this case the assignatory particle TI is acting as a copula, telling us that Peter is a boy.

- for the second modifier object - siòiset - the ephemeral particle SI informs us that Peter 'posesses' (a better translation is some form of the verb 'to have', which otherwise does not exist in the language) a quantity of years.

- the final modification supplies us with the number of years - ehnatis (sixteen) - that Peter posesses; note that numbers (between 1 and 63) can be directly attached to the objects they quantify using the concatenative particle E.

Using modifying particles as copulas

Ákat lacks a formal copula (such as the Ramajal verb 'to be'); instead, the language uses various modifier particles - known as the adjective group - to play the role of the copula:

- the descriptive particle LI - which combines with the object's class particle irregularly: liw, lij, tl, lin, sl - is commonly used to indicate that the head noun has the physical qualities of the modifying noun

- the assignatory particle TI is used to assign the physical qualities of the modifying noun to the head noun

- the metaphorical particle CI assigns the metaphorical or philosophical aspects of a modifying noun to the head noun, rather than the physical, sensory aspects - good translations for this particle are 'like' and 'as'

- ácusliỳfux

- black dog

- ácustiỳfux

- the dog is black

- ácusciàkif

- the dog is like a horse

- ácusliétos

- friendly dog

- ácusnineityftiátosêfàsninake!

- this dog is my friend

"How old are you"

Age is generally counted in òiset (years), and is assigned to a person using the ephemeral particle SI. If the age is less than 64, the number can be used to modify òiset using the concatenative particle E.

- cuáke!siòiset

- how old are you?

(note the lack of a question mark - the interrogative particle CU is enough to inform people that this is a question, thus negating the need for additional punctuation).

- nake!siòisetehnatix

- I am twenty years old

- òikolehnatix

- [years] twenty (using a reference object)

- hmhnatix

- Twenty! (with emphasis)

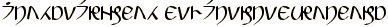

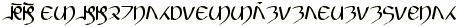

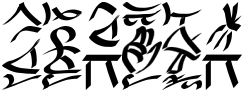

àke!tiáfushne! nilákiskinyfekhnest jækeʔtiwæfʊsŋeʔ niækiskinafekŋest àke! .ti .áfus .hne! nil .ákis .ki .nyfek .hnest he.1 .M-ASSG .SG.student .REMAIN O-BENEFACT .SG.person .M-ASSC .UN.law .BECOME He[P] is a student, [studying to become] a lawyer

Action avoidance

Some objects - such as 'student' - infer a particular action above all others: the key purpose of a student (some would argue) is to study. Ákat speakers will often choose to employ such an object rather than the action, allowing people to infer that an action is involved in the clause from the context in which the object is presented.

In this example, action avoidance is achieved with the help of two grammatical tricks. The first is to introduce the trade that Peter is studying as an oblique object introduced by the benefactive particle nil-; normally this particle will indicate the object that benefits from the action undertaken in a clause but in this case, where the action is being implied rather than explicitly stated, the particle indicates that the oblique object is the desired outcome for the benefit of the direct object (Peter).

The second trick bought into play is the assignation of existential suffixes to each object to show the progression of the implied action: Peter is a student -hne!, now; he will become a lawyer -hnest, in due course.

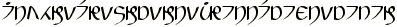

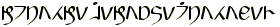

àke!siáfixstiskiỳfakkátankitapas jækeʔsiwæfiʃstiskijafæʔkwætænkitæpæs àke! .si .áfixstis .ki .ỳfakkát .an .ki .tapas he.1 .M-EPHM .SG.cousin(distaff) .M-ASSC .UN.hearing .NAME .M-ASSC .SG.the He[P] has a cousin [mother's side] called Simon

Alternate third personal objects

In Ramajal sentences it is often possible to disambiguate which pronouns reference which objects according to the sexual gender or number of the object (he, she, it, they); in other languages the class or lexical gender of a noun will determine which pronoun gets assigned to the object in subsequent clauses. Ákat employs a rather different system, known to Ákat grammarians as personal reference swapping.

In the Ákat system, the first person introduced into the discourse (who is not the speaker, I, or listener, you) is assigned to the natural things personal object àke!; the next person is assigned to the dangerous things personal object sake! - also known as the fourth person. If another person is introduced they generally get assigned to àke!, and so on, with the assignations alternating between the two.

Occassionally a new person will be assigned to the made things personal object take!, though such an assignation often carries derogatory connotations - the speaker (and hopefully the listener) does not care much for that person, or holds them in low regard.

In this instance, we are being introduced to Simon - made explicit by modifying his name with a demonstrative object; as the second person intruduced during this discourse we should expect that, according to the rules of personal reference swapping, whenever we come across the personal object sake! we are talking about Simon, not Peter (who has already been assigned to the personal object àke!).

cirivz àke!fiétap fysake! χiɹivz jækeʔfiwetæp fasækeʔ ciri .vz àke! .fi .étap fy .sake! [+IND.NONP.COMP] .SCOPER he.1 .M-COMP .PC.taller O-PARTITIV .he.2 He[P] is taller than him[S]

The pro-verb VZ

The pro-verb vz - also known as the scoper particle - is most often met when acting as the concatenator between two clauses. Normally the conjunction used to join the clauses is prefixed to the verb of the second clause - in Ákat the clause conjunctions are an integral part of the action prefix; however, in verbless clauses there is no verb to carry out this function. In such situations the pro-verb is deployed and the appropriate action prefix is attached to that.

Unlike other verbs, the pro-verb is tightly restricted in the particles that can be affixed to it. In addition to the action prefix, the only other particles it can take are the evidentiality markers: -oks - 'it is known that ...'; or -eqs 'it is believed that ...'.

Do not confuse clause conjunctions with list conjunctions: the former are handled by action prefixes; the latter are dealt with by object modifier particles.

Making comparisons in a verbless clause

Ákat employs a fairly rigid phrase template to allow a given quality of two objects to be compared, without the need to use a verb or a copula:

scope-vz focus-fi-quality fy-standard

- the commonest scope for comparison is the scope of quantity - cirhm- ciri- corihm- curi- xacorihm- xacuri- cuxacorihm- cuxacuri-

- the focus is the subject of the comparison

- the quality is the issue of the comparison

- the standard is the object to which the the focus is being compared

Only mass nouns which use the noun number system to demonstrate their intensity can be used as the quality value in the phrase - for example: nycux, weight; nycyt, blueness; ýfuc, sweetness; tyhnkat, noise; nykes, temperature; ýkif, speed; ýkoc, cleanliness; tyhnkyk, fairness or equatability; ýpax, helpfulness; syhntap, width; tyhntap, depth or distance; ýtap, height; etc.

Examples:

- scope-vz focus-fi-quality fy-standard

- cirivz àcusfiétus fyàxuq

- The dog (àcus) is bigger (étus) than the cat (àxuq)

- cirivz ỳfakkátanfiékif fysatexan

- Simon (ỳfakkátan) is faster (ékif) than Peter (satexan)

- cirhmvz nake!fineiqokhmpet fyáke!

- I (nake!) was more respected (neiqokhmpet) than you (áke!)

The number of the quality generally determines whether it is being used as a comparative or a superlative, for instance: fiútap, shortest; fiátap, shorter; fiétap, taller; fiótap, tallest. The superlative template is similar to the comparative template, without the standard at the end:

- scope-vz focus-fi-quality

- cirivz àcusninutyffiótus

- That dog (àcusninutyf) is the biggest (ótus)

- cirivz ỳfakkátanfiókif

- Simon (ỳfakkátan) is the fastest (ókif)